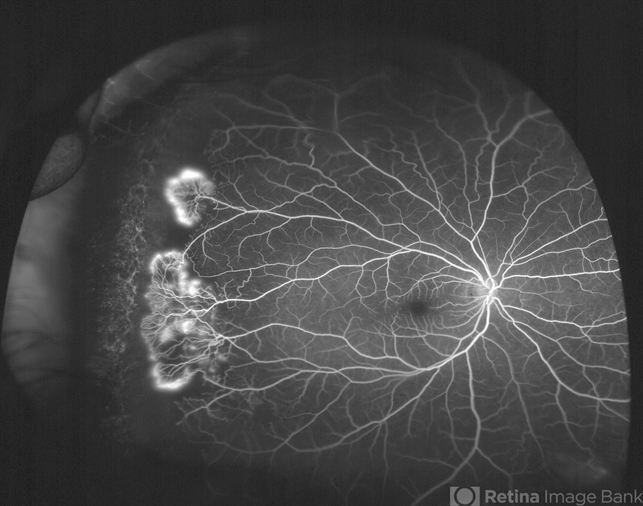

Sickle Cell Retinopathy case

In the world of optometry, we often look into the eyes and see more than just vision—we see health, disease, and sometimes, the fragility of life itself. Sickle Cell Retinopathy (SCR) is one such condition where systemic disease leaves devastating footprints on the retina. A striking reminder of this was the case of a 19-year-old male with Stage V proliferative sickle retinopathy (PSR), whose vision was compromised by a combined tractional and rhegmatogenous retinal detachment—a tragic, yet not uncommon scenario in advanced disease.

As Dr. Mateus Queiroz Corrêa powerfully stated:

“When hemoglobin twists, vision unravels.”

Let’s dive into what that really means for the eye and how optometrists can help recognize, monitor, and co-manage this complex retinal condition.

What is Sickle Cell Retinopathy?

Sickle cell retinopathy is a microvascular complication of sickle cell disease (SCD), most commonly seen in patients with HbSC and HbSS variants. As red blood cells sickle and deform, they block the fine arterioles of the peripheral retina, leading to ischemia. In response, the eye initiates a pathological repair process that unfortunately causes more harm than healing.

Molecular Insight: Why the Retina Suffers

The sickled erythrocytes obstruct retinal capillaries, particularly in the periphery, inducing:

Retinal ischemia → triggers VEGF (Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor) release VEGF promotes abnormal new vessel growth — the characteristic sea-fan neovascularization These fragile vessels are prone to bleeding and eventually become fibrotic Fibrosis contracts, pulling on the retina Retinal tears form, and subretinal fluid accumulates → leading to combined tractional and rhegmatogenous retinal detachment (RD)

Notably, patients with the HbSC variant often have higher blood viscosity, making them more susceptible to proliferative retinopathy despite milder systemic symptoms compared to HbSS.

The Stages of Proliferative Sickle Retinopathy (Goldberg Classification)

Understanding the progression helps clinicians anticipate complications:

Stage I – Peripheral arterial occlusions Stage II – Arteriovenous anastomoses Stage III – Sea-fan neovascularization Stage IV – Vitreous hemorrhage Stage V – Retinal detachment (tractional ± rhegmatogenous)

Clinical Case Recap

Patient: 19-year-old male

History: HbSC sickle cell disease

Findings:

Case Summary:

- History: Sickle cell disease (HbSC)

- Fundus: sea-fan neovascularization → fibrosis → traction

- Retinal break with subretinal fluid = combined RD

- Surgical management planned: pars plana vitrectomy with membrane dissection and tamponade

This illustrates how quickly Stage III disease can evolve into Stage V if left untreated or unmonitored.

Management Pearls for Optometrists

Optometrists play a vital role in early detection and referral. Here’s what to keep in mind:

Early Stages (III-IV): Refer for panretinal photocoagulation (PRP) or intravitreal anti-VEGF injections Monitor closely for vitreous hemorrhages Advanced Stage (V): Urgent referral for pars plana vitrectomy Membrane peeling, break repair, and retinal tamponade are critical Counsel on systemic care: Co-manage with hematologists Address anemia, hydration, and overall systemic control In the clinic: Use wide-field imaging to monitor periphery Educate patients—symptoms like flashes, floaters, or sudden vision loss need immediate attention

Avoid excessive intraocular pressure during exams—fragile vessels may bleed with even minor manipulations.

Prognosis and Outcomes

Visual prognosis in Stage V SCR is guarded, depending on:

Macular involvement Chronicity of the detachment Surgical timing and postoperative care

Interestingly, outcomes in HbSC patients can sometimes be better than in HbSS due to less chronic retinal ischemia—but the recurrence risk remains high across all genotypes.